Figure 1: Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo, Japan (McCurry 2021)

Nakagin Capsule Tower was designed by Kisho Kurokawa, a pioneer of Metabolism and capsule architecture who studied at Kyoto University and the University of Tokyo, under the supervision of Kenzo Tange. The tower is one of the few metabolist concepts that were ever realized, belonging to the architectural movement of the 60s and 70s, Metabolism, which appeared as a counteraction to the westernization of Japan after the Second World War (Ishida 2015).

As the Greek term ”metabole” is directly translated to ”change”, metabolists were implementing the old Shintoism’s philosophy of periodic renewal (Lin 2011) into contemporary buildings. The movement viewed the city similar to a living organism whose cells are represented by buildings that are constantly renewed. They were opposed to the modernist approach to planning which envisioned a specifc, physical destination for the city’s development and rather relied on patterns that could be followed consistently over time in order to constantly adapt to the new needs of the population (Lin 2011).

Figure 2: Takara Beautilion, 1970 World Expo Osaka, Japan (Lin 2011)

Kisho Kurokawa frst explored his ideas for capsule housing at the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka while designing Takara Beautilion. The building was based on his ”Capsule Declaration” which envisioned a new form of living and ’an entirely new family system centred on individuals’ (Michael, Yaacob, and Ali 2018) rather than traditional family units. The building consisted of a number of prefabricated cubic capsules installed on a steel framework with connectors and was put on site in only six days (Lin 2011). The structure had an incomplete look to emphasize on its expandability.

Torizo Watanabe, president of the real estate firm Nakagin Co. at the time, visited Osaka Expo and was so impressed that he wanted to have a building for his firm designed by Kurokawa (Lin 2011). Watanabe envisioned the development mainly for ‘small or medium business owners and high-level employees, who already owned a house or apartment and looked for a space in Tokyo’s center city as studio or for occasional overnight stay’ (Lin 2011). This was a great idea since even in the 70s Tokyo was already big and many people did not have time to go home due to the intense work culture.

Nakagin Capsule Tower was constructed in a year and fnished in 1972. It ‘consists of two towers at eleven and thirteen stories respectively as well as 144 capsules’ (Lin 2011). Only the two towers and space for utilities and equipment were built on-site, the capsules came prefabricated (Lin 2011). Each capsule was installed independently, ‘tied to one of the concrete cores with only four high-tension bolts: two each on the upper and lower sides’ (Lin 2011) and was able to hang of the shaft without afecting others in order to replace them if needed.

Figure 3: The construction of Nakagin Capsule Tower (Lin 2011)

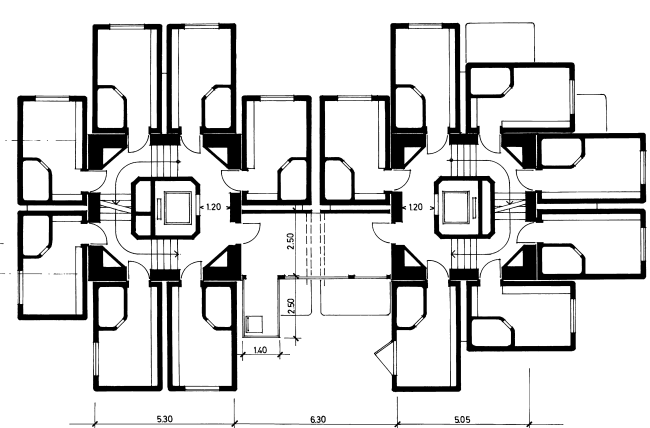

Figure 4: Floor plan of Nakagin Capsule Tower (Lin 2011)

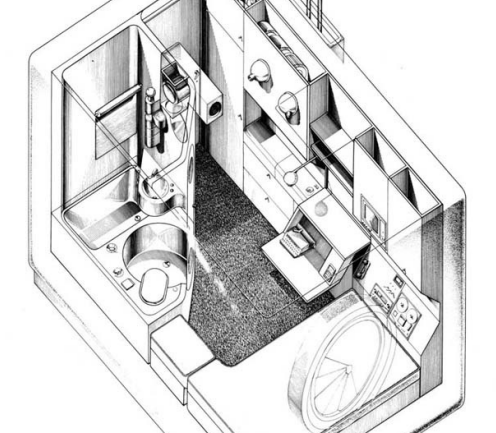

The size of one capsule is of a shipping container (Lin 2011), compact for easier transportation, ‘designed in tatami module proportions of 4×2.5 meters’ (Ishida 2015). The prices ranged from $12,300 to $14,600 for one capsule, ‘about the cost of a luxury car of the time’ (Lin 2011). The utilities were also minimal due to the small space: a bathroom unit, a single bed, a cabinet which included a TV, radio, a telephone, an air cleaner, an air conditioner, a stove, a refrigerator and a desk calculator (Lin 2011).

Figure 5: The interior plan of a capsule from Nakagin Capsule Tower (Lin 2011)

On 12th of April 2022 the demolition of the Tower had started, against the many eforts of some tenants, architects and even Kurokawa himself. Even back in 2007, ‘80 percent of the capsule unit owners voted in favor of demolishing the building and replacing it with a more proftable 14-storey building’ (Ishida 2015), with 60% more foor areas (Lin 2011). While Nakagin Capsule Tower was listed as an architectural heritage site in 2006 by DoCoMoMo, this unfortunately does not provide legal protection against demolition (Ishida 2015).

Due to the poor condition of the Tower, in 2021, only 20 tenants have remained (McCurry 2021). Even though it was planned ‘that the main shafts would last at least sixty years, while the capsules would be due for replacement in twenty-fve to thirty-fve years’ (Lin 2011), no replacement has ever taken place.

Hiroshi Watanabe, an architecture critic, commented in 1980 that ‘Any capsule is supposed to be replaceable ‘theoretically,’ without disturbing the others. There are three things that might, however, stand in the way: money, other owners, and the architect’s own design’ (Ishida 2015). To replace one capsule or repair the pipes, other capsules also had to be taken away, which required the approval of multiple residents. Moreover, even when ‘the Tower was only eight years old, the estimated cost of the capsule would have been three times the original construction cost of $4,500 each’ (Ishida 2015) and during recent years it went up exponentially.

There were many issues with the building throughout the years: no operable window, which meant the capsules were completely dependent on mechanical system, poorly insulated thin walls, the dangers of asbestos, water leakage due to the difculty of reaching to the utilities pipelines that were attached on the exterior, which also lead to the building not having hot water anymore, many abandoned capsules with moldy ceilings and walls, leading to the fear of collapsing at an earthquake (Ishida 2015).

Overall, it was more proftable to demolish the building entirely and build a new one, a very common practice in Tokyo. In fact, the city ‘continues to renew itself at the rate that around 30% of its structures are replaced in every ten years’ (Lin 2011).

Nevertheless, did Nakagin Capsule Tower fulfll its purpose? Some would claim that Nakagin Capsule Tower failed as a metabolist building, that it did not ‘live up to its principals that made it landmark-worthy in the frst place – the idea of the metabolic cycle, interchangeability, and adaptability’ (Ishida 2015). However, that is not entirely true.

Tatsuyuki Maeda, former resident of Nakagin Capsule Tower, who ran campaigns over the years in order to prevent the Tower and the capsules from demolition, saved 23 of the capsules he owns, from which 14 are under full restoration (Brandoli 2022). He hopes to give them a new life in new settings, such as permanent housing, hotels or museums. There is a total of 36 capsules left from the demolition, with a possibility of building new ones as well if there is enough demand, according to Maeda (Brandoli 2022).

It is also noteworthy mentioning Capsule House K, built in 1973 as Kurokawa’s villa with the same concept as the Tower: a central core shaft using four capsules from Nakagin Capsule Tower’s construction, attached around it (Angelopoulou 2021).

Figure 6: Capsule House K, Nagano Prefecture, Japan (Angelopoulou 2021)

These two elements show the versatility of the capsules and the multiple roles they can take for a ‘more conscious use of material and industrial technology’ (Lin 2011). The spirit of capsule architecture is deeply ingrained in Japanese culture, courtesy of Kisho Kurokawa himself, who kept putting his concepts into practice. The frst ever hotel with sleeping capsules, Capsule Inn Osaka, was built by Kurokawa in 1979, as a response to the increasing need for a cheap night in high density cities (Michael, Yaacob, and Ali 2018). This has set the trend for other capsule hotels, in Japan, but also in other parts of the world.

Figure 7: 1979 sleep capsule design from Capsule Inn Osaka, Japan (Michael, Yaacob, and Ali 2018)

All in all, from a western view of seeing architecture, one could argue that Nakagin Capsule Tower failed as a project since it did not withstand the test of time. However, Japanese culture values the end product less than ‘the process of craft that is passed on for generations’ (Ishida 2015). With his ideas, Kurokawa has achieved ‘permanence through impermanence’ (Ishida 2015), being considered ‘one of the frst to materialize Japanese spatial and philosophical ideas into modern buildings’ (Ishida 2015).

By having Buddhist ideas and Shintoism philosophy embodied in the building, Nakagin Capsule Tower is a pure example that architecture goes through a continuous timeline instead of a progressive one, in which ‘present, past and future are not chopped of from one another but merge into one uninterrupted fabric’ (Popescu 2022), a concept brought by Sigfried Giedion, a historian of modernist architecture. The Tower is undoubtedly an architectural heritage, a source of inspiration for a more sustainable, economical and practical architecture, by learning from what went wrong in order to improve on Kurokawa’s ideas.

References

Angelopoulou, Sofa Lekka (2021). “kisho kurokawa’s metabolist ’capsule house K’ from the 1970s to be preserved in Japan”. In: url: https : //www.designboom.com/architecture/kisho-kurokawa-metabolistcapsule-house-k-1970s japan-04-12-2021/.

Brandoli, Lucia (2022). “Nakagin Tower capsules saved from demolition are now on Airbnb (and more)”. In: url: https://www.domusweb.it/en/ news/2022/11/29/tokyos-nakagin-capsule-tower-cubes-willget-a-new-life.html.

Ishida, Aki (2015). “Paradox of a Landmark that is not: the life of the Nakagin Capsule Tower”. In: International Conference on East Asian Architectural Culture.

Lin, Zhongjie (2011). “Nakagin Capsule Tower and The Metabolist Movement Revisited”. In: Architectural Education 65, pp. 13–32.

McCurry, Justin (2021). “Decaying but beloved, Tokyo’s Capsule Tower faces uncertain future”. In: url: https://www.theguardian.com/world/ 2021 / nov / 09 / decaying -but -beloved -tokyos -capsule -tower faces uncertain-future.

Michael, Gilbert, Naziaty Mohd Yaacob, and Zuraini Md Ali (2018). “The capsule living unit reconsidered a Utopia transformed reality”. In: Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities 26.3.

Popescu, Carmen (2022). “A Genealogy of Architectural History’s Flattening: A Perspective from Post-History”. In: Architectural Histories 10.1.