1. Introduction

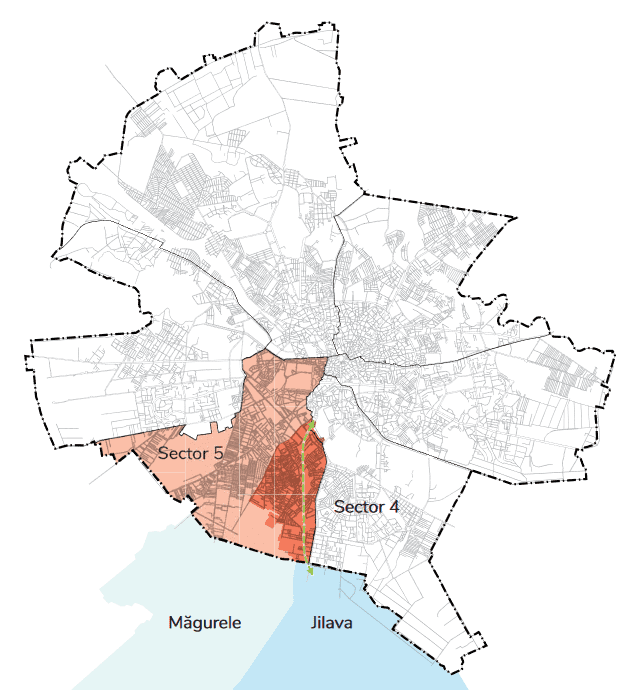

Ferentari is a neighborhood in southeast periphery in Sector 5 of Bucharest, Romania with an estimated population of 75,000. Once a marginal area, Ferentari has evolved into one of Bucharest’s most marginalized urban zones. Sector 5 is exhibiting the starkest housing inequality in the city, where Ferentari’s poverty is neighbouring the affluence of areas such as Cotroceni. Over 20% of its residents, approximately 18,200 people, live below the poverty line (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

This essay delves into Ferentari’s history and current state, analyzing it through the lens of systemic and contingent marginalization theories explained in “Concepts in Social and Spatial Marginality” (Mehretu et al., 2000). The analysis will extend to the impact of municipal and NGO initiatives, contrasting their approaches and effectiveness, aiming to understand and address the deep-rooted issues of marginalization and inequality in Ferentari.

2. Systemic and contingent marginalization theory

I will examine the current situation of Ferentari through the marginalization theory in “Concepts in Social and Spatial Marginality”. Marginality refers to a multifaceted state of disadvantage that affects individuals and communities, characterized by exclusion from society and a lack of access to resources and opportunities (Mehretu et al., 2000. One type of marginality is perpetuated by societal norms and power structures that systematically disadvantage certain groups usually based on class, ethnicity, age, gender. It is named “systemic marginality”: a deliberate social construct maintained to exert control and enforce social exclusion and economic exploitation (Mehretu et al., 2000. In contrast, contingent marginality arises from the unpredictable nature of the free market, where individuals and communities are disadvantaged due to factors such as “unattractive locations, cultural restrictions, inadequate labour skills and lack of useful information” (Mehretu et al., 2000). To understand the systemic and contingent marginalization in Ferentari, historical context and current data is needed.

3. Historical context

The first mention of the name Ferentari was in 1832, attributed to the current street, Calea Ferentari, which back then, used to be a border of the city. The region’s exclusion from Bucharest’s laws encouraged the middle-lower class to settle, forming a semi-rural community without essential utilities (VOINEA et al., 2022).

Post-World War I, the area, known as “Campul Veseliei,” was struggling with poor sanitation and high epidemic risks, leading to early urban planning efforts. Unfortunately, the cost of expropriating the existing homes was too high for the plan to be carried out (VOINEA et al., 2022).

After World War II, in 1946, Ferentari underwent significant changes during an extensive project, driven by the socialist realism trend at that time, as the new communist state wanted to show its power and commitment for the working class. Large collective spaces, public buildings, as well as the “red blocks” were built for 600 families (VOINEA et al., 2022).

One of the turning points in the development of Ferentari was the devastating 1977 earthquake. Many buildings were damaged, and another systematization of the area was necessary. Ferentari has reached 230,000 residents in 1980, making it “one of the most important residential zones of Bucharest” (VOINEA et al., 2022).

When the communist regime fell in 1989, the plan schemes of the neighbourhood stagnated, factories were closing, which resulted in a lot of workers that lost their jobs to move out of Ferentari. Many apartments were abandoned, which they eventually became informally occupied by very impoverished people (Harris and Vorms, 2017).

4. Recent state of Ferentari

4.1. Population

Figure 1. Figure 1. Map of Bucharest, the dark orange color covers Ferentari neighbourhood and the light orange covers the rest part of Sector 5 (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Table 1. Comparative urban statistics in 2019 (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

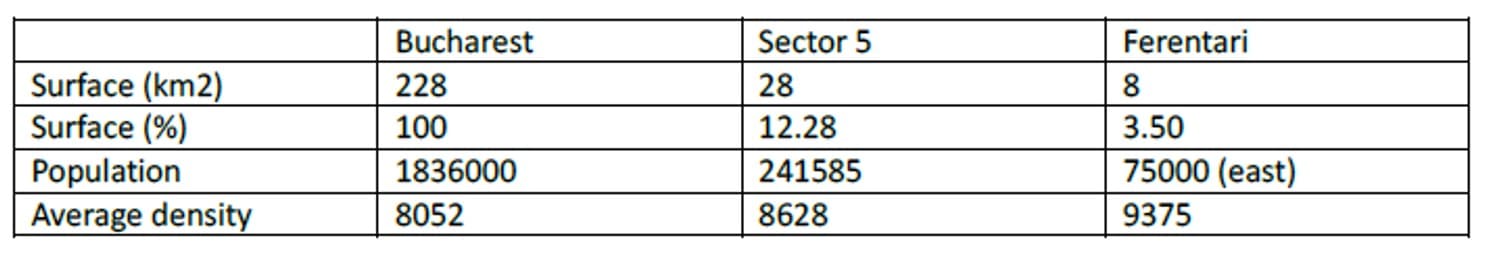

The population in the northern part of Ferentari, which consists of abandoned industrial lands, is quite low. The more densely populated part is in the centre of the neighbourhood with overcrowded areas mainly inside the “Marginalised Urban Zones”(Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019). The southern part is sparsely built-up, but is beginning to expand urbanization due to the construction of single-family housing over the past decade (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

However, the effectiveness of EIA relies mostly on national environmental laws and objectives. Biases, inconsistent data quality, and diverse global standards can impact its framework.

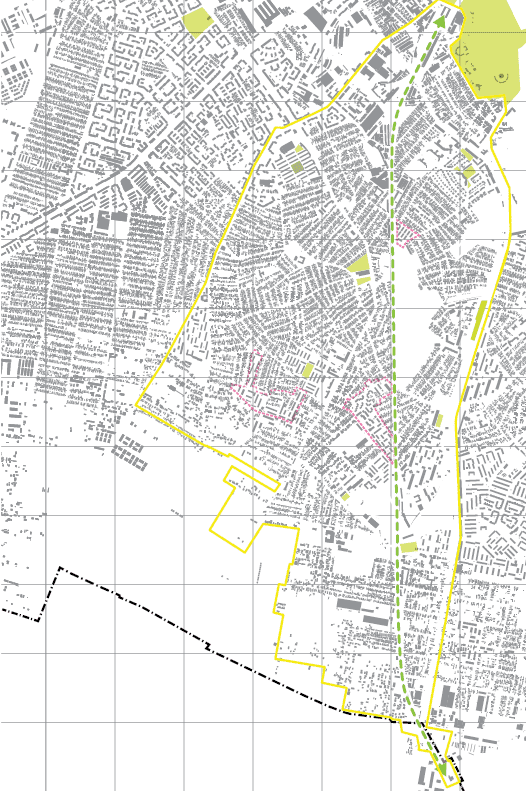

Figure 2. There is a noticeable difference in population density inside the 1 km grid. The borders of Ferentari are marked with yellow (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Sector 5 has the youngest population in Bucharest, as the general trend of the capital is of demographic ageing. The number of young people under 14 for every 100 people over 65 is 130% in Sector 5, compared to the 85% average in Bucharest. Ferentari reaches a level of 150-180%. However, a lower average age may also suggest a lower life expectancy of older people, correlating with poorer health in the area (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

51.5% of the Roma population in Sector 5 lives in areas that overlap with Ferentari (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

4.2. Housing

In Ferentari, the proportion of dwellings with at least 5 people living in them show percentages as high as 18.7%, while in Bucharest they are 8.5% and 12.6% in Sector 5. More than 14% of dwellings have no bathroom in Ferentari. The predominant type of housing are low-rise single-family houses, taking around 68% of the entire surface zone (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

The most inadequate housing in the area is located inside the “Marginalized Urban Zones” (MUZ) (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019), representing 4.2% of the total inhabited territory in the neighbourhood, home to about 20,000 (24%) of the people in Ferentari with incomes below the poverty line. The housing inequality in Ferentari is most visible in the MUZ, given the degree of decay, overcrowding and lack of proper utilities of the blocks. Originally built as a temporary low-comfort living for workers and students, these blocks are now housing families with an average of 3.8-4.1 members, with the average floor area between 4.1 and 9.2 sqm per person, below the average of 21,39 sqm/person in Bucharest. This led to many informal interventions, for example, extensions on the facades or bathrooms built by tenants inside dwellings (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Multiple generations continue to live in these areas, with instances of two or even three generations of adults who were born and raised in the MUZ (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019), indicating a significant challenge for residents in breaking the cycle of poverty.

Figure 3. MUZ in Ferentari: poorly maintained public spaces and informal extensions due to overcrowding (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

4.3. Social infrastructure

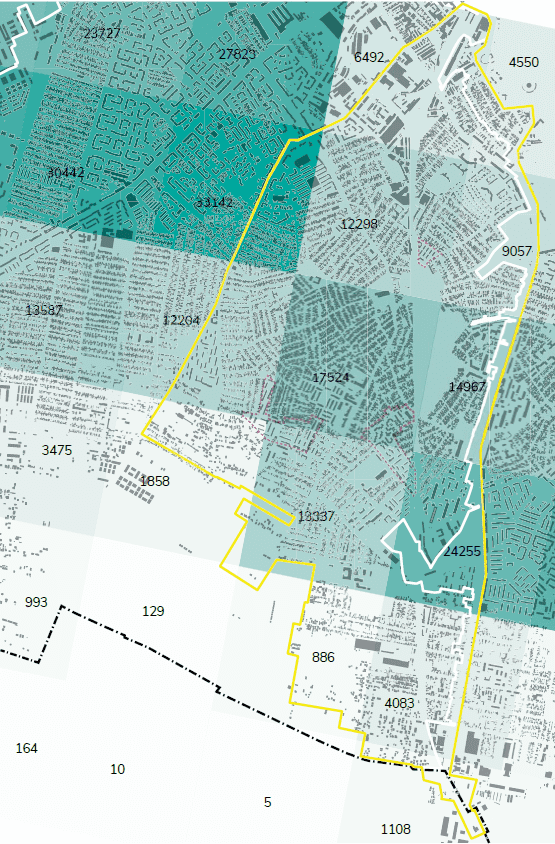

Educational, medical, and recreational facilities are insufficient in the neighbourhood. The southern part is lacking almost all public facilities, despite new residential areas being built over the past 30 years that would require complementary services and facilities (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Figure 4. Facilities in Ferentari within a radius of 500 m (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

4.3.1. Green public spaces

There is a critical lack of green spaces and public parks throughout Ferentari, currently covering only 1% of the study area. They play a vital role as social spaces, contributing to a better quality of life (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Figure 5. Public green spaces in Ferentari (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

4.3.2. Education

Bucharest averages 33.7% in higher education, Sector 5 has the lowest rate at 26.3%, with areas such as Ferentari dropping to 9.7%. Major disparities are revealed through data, there are more than 50% graduates in some areas (Panduri, 59% or Cotroceni, 56%), but the percentage drops to 9.7% in Ferentari. There is also a high number of illiterate people in Ferentari (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Looking at the social infrastructure map, it is visibly clear that there is a reduced interest in higher education in the area. On a 4 km radius from the center of Ferentari, there is only one university. All 4 high schools in the neighbourhood are located at the edge, compared to the 6 schools and 10 kindergartens scattered across the entire Ferentari.

The percentage of women staying at home is higher in the neighbourhood compared to other areas. While Bucharest’s average is 11.4%, Sector 5 reports an average of 15.4%, with certain regions adjacent to the Ferentari witnessing rates between 20-29%. Daycare facilities opened by the Social Welfare Department did not reach the expected number of enrolments. Contributing factors to the current situation may include cultural dynamics as well as the limited education and skills among women, suggesting a heightened risk for families reliant on a single income and an even more unstable condition for single-parent households (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Another explanation for lack of proper education in the area might be people’s reluctance to formally register their children with state authorities. Poor families tend to send their children to work early either to assist with household chores or to contribute with an additional source of income. Education is compulsory until the end of high school and non-compliance can result in substantial fines ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 lei (LEGEA învățământului preuniversitar, 2023), unaffordable for poor families. To avoid the financial burden of fines, parents may choose not to legally register their births, thereby keeping the children out of the formal education system.

These factors collectively contribute to low labor market inclusion rates and a tendency for people to resort to working for the illegal markets.

4.3.3. Transport

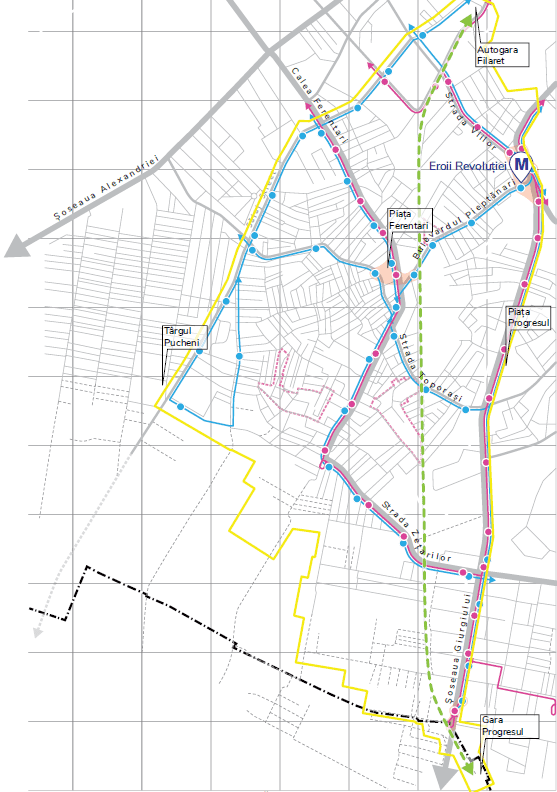

Public transport is decent, especially in the north-south direction, along the main boulevards of the district. Nonetheless, the limited east-west transportation links and the disruption by large private-owned industrial areas make traversing the railway corridor significantly challenging for residents. Although urban transportation is easily accessible, the routes are not optimised for residents to access specific destinations for certain services or facilities which they may lack close to where they live. This can impact on all aspects of life, negatively affecting its quality. Additionally, there is an absence of metro lines in the area (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

Figure 6. Public transport in Ferentari. The blue dots are bus stations, and the red ones are tram stations. The only metro station in the area is Eroii Revoluției, at the northern edge of the neighbourhood (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

4.4. Real estate

House prices in Ferentari are half compared to those in the north of Bucharest. Even though office rents in the south are more affordable, the abundance of vacant spaces suggests a lack of demand, attributed to limited interest in this area. This situation contributes to the concentration of disadvantaged individuals to reside there (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

All the issues mentioned above related to the state of housing and social infrastructure, coupled with its negative reputation related to crime and poverty, contributes to the Ferentari’s inability to attract investment from private developers, despite the large available land (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

5. Systemic and contingent marginalization theory applied to Ferentari

The application of Assefa Mehretu et al. theory is noticeable in various social and economic dimensions in the neighbourhood mentioned above.

Systemic marginalization is visible through deep-rooted disparities, resulting from a lack of implication from responsible authorities for improving the quality of the neighbourhood. This form of marginalization is ingrained in societal norms and stereotypes, particularly affecting ethnic minorities and women. This is most evident in the “Marginalized Urban Zones”, where overcrowding and lack of basic facilities are common.

Contingent marginalization in Ferentari exists because of the economic situation. The high unemployment rates and reliance on the informal market, resulted from inadequate educational infrastructure, indicate the neighbourhood’s vulnerability to market fluctuations. Additionally, the lack of easy access to certain destinations by public transport further exacerbates this marginalization, hindering residents’ ability to access more employment options and other opportunities.

6. Addressing housing inequality

6.1. The international right to adequate housing

Adequate housing is a fundamental human right deeply embedded in various international legal frameworks, actively promoted by entities such as the UN-Habitat. Under the United Nations, this agency is tasked with fostering sustainable urban development, ensuring everyone has access to proper shelter. Its mandate aligns with the Habitat Agenda, emphasizing governmental responsibility in realizing the right to adequate housing. This right, integral to an adequate standard of living, has been recognized in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Every country has committed itself to upholding the right to adequate housing, having ratified at least one international treaty that includes references to adequate housing (Bayefsky, 2000).

Adequate housing goes beyond mere shelter. It encompasses the right to live in “security, peace and dignity, including non-owners of property” (Bayefsky, 2000). This includes: “security of tenure”, “availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure”, “affordability”, “habitability”, “accessibility”, “location”, “cultural adequacy”, which are fundamental in defining what constitutes adequate housing (Bayefsky, 2000).

These criteria are crucial to prevent homelessness and protect against human rights abuses. Those lacking the rights to education, employment, or social security are particularly vulnerable to housing insecurity, as it is a prerequisite to those rights (Bayefsky, 2000)).

While it is understood that the full realization of this right might be constrained by resources and require time, states are obliged to demonstrate constant progress towards this goal, with “all appropriate means” (Bayefsky, 2000). This includes legislative measures, effective monitoring of housing conditions, protection against forced evictions, and offering solutions for violations of housing rights. Moreover, international assistance and cooperation play a vital role, especially when a state lacks the capacity to fulfil these requirements independently (Bayefsky, 2000).

Inadequate housing is still prevalent in Ferentari, yet the municipality and non-governmental organizations are making efforts to address the fundamental human rights.

6.2. Government initiatives

There are two recent implemented projects made by Sector 5, one to encourage more participation in education and reduce school quitting in the area, and the other one to train school staff (“Arhive Proiecte implementate,” n.d.).

Other relevant projects that are still going are for the implementation of anti-corruption preventive measures, the establishment of new preschool classes, increase the quality of life of Roma communities in marginalized areas by improving health, education and reducing discrimination (“Arhive Proiecte implementate,” n.d.).

The most relevant project tackling the issues of housing and social infrastructure is the urban development and regeneration plan for Ferentari, elaborated by the World Bank. The report shows extensive proposals and solutions to increase the living quality of the area (Chyi-Yun Huang et al., 2019).

All these plans look great on paper. However, there are no reports on the aftermath of them on the official website of Sector 5, displaying a lack of honesty and transparency of the municipality.

6.3. Non-governmental initiatives

Casa Bună Association is an NGO working with children from vulnerable areas in Bucharest, particularly Ferentari, for over 16 years (“Cărți dăruite de copii au ajuns la Casa Bună a lui Valeriu Nicolae,” n.d.). The association’s work has shown tangible results in changing children’s lives by supporting their education, offering medical assistance and basic needs, and developing their various skills (“Asociația Casa Bună | Raport anual 2022,” n.d.). For example, a report in 2022 shows all the association’s achievements and miscalculations during that year. Some of the accomplishments were providing school lessons, school camps, workshops, medical treatments, meals, clothing, home appliances and school supplies (“Asociația Casa Bună | Raport anual 2022,” n.d.).

7. Conclusion

Examining Ferentari through the theory about systemic and contingent marginalization reveals profound social and economic disparities, primarily in the “Marginalized Urban Zones”.

The efforts made by the municipality, like urban regeneration plans and education programs, show promise, but their effectiveness remains unclear due to a lack of transparency. NGOs initiatives have shown more direct and noticeable results, as they have a much stronger willingness for change and more engagement with the local community. Notwithstanding, community organizations tend to be understaffed and underfunded, compared to governmental ones, which can negatively impact the implementation of the projects.

Addressing these issues requires comprehensive strategies that tackle the underlying causes of marginalization, ensuring an equitable and sustainable development for Ferentari.

References

Arhive Proiecte in implementare [WWW Document], n.d. . Primăria Sector 5 Bucuresti. URL https://sector5.ro/category/proiecte/proiecte-in-implementare/ (accessed 1.15.24).

Asociația Casa Bună | Raport anual 2022, n.d. . Asociatia Casa Buna. URL https://asociatiacasabuna.ro/raport-anual-2022/ (accessed 1.15.24).

Bayefsky, A.F., 2000. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, in: Bayefsky, A. (Ed.), The UN Human Rights Treaty System in the 21 Century. Brill | Nijhoff, pp. 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004502758_044

Cărți dăruite de copii au ajuns la Casa Bună a lui Valeriu Nicolae [WWW Document], n.d. . IQads. URL http://www.iqads.ro/articol/49340/carti-daruite-de-copii-au-ajuns-la-casa-buna-a-lui-valeriu-nicolae (accessed 1.15.24).

Chyi-Yun Huang, Marina Batog, Ana Bulai, Bogdan Suditu, Iulian Canov, Mihai Șercăianu, Ana-Maria Elian, Vlad Stoica, Tamina Lolev, 2019. Soluții urbane practice pentru cartierul Ferentari.

Harris, R., Vorms, C. (Eds.), 2017. What’s in a name? Talking about urban peripheries, Global suburbanisms. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ; Buffalo ; London.

LEGEA învățământului preuniversitar, 2023.

Mehretu, A., Pigozzi, B.W., Sommers, L.M., 2000. CONCEPTS IN SOCIAL AND SPATIAL MARGINALITY. Geografiska Annaler.

VOINEA, A.R., DOLGHIN, D., PULAY, G., 2022. Ferentari incomplet – Politici urbane la o margine de oras 1846-2011.