Introduction

Itsukushima Shrine, a prime example of Japanese spiritual culture and aesthetics, offers deep insights into the country’s heritage. Situated on an inlet of Miyajima Island, also known as Itsukushima, the shrine is often referred to as Aki no Miyajima. Located in Hiroshima Bay within the Inland Sea, this island is home to Mount Misen, the region’s highest peak (Cartwright, n.d.). The shrine’s structures, meticulously restored to preserve their twelfth-century character, include six National Treasures and eleven Important Cultural Properties, with the World Heritage site covering fourteen percent of the island (Joseph Cali et al., 2013).

History of Itsukushima Shrine

Since ancient history, Itsukushima Island and its mountain were considered holy; access and construction were prohibited. Shrines were built on the shores, and priests only travelled there for rituals (Utaka, 2015). A policy still theoretically upheld, births, deaths, and burials were not allowed to preserve the purity of the island (Cartwright, n.d.).

A simple Shinto shrine on the island was likely first established by local Sherman. It was significantly developed in 593 CE, although its proof of existence is from 811 CE (Cartwright, n.d.). Originally dedicated to the three daughters of Susanoo, the Shinto storm god, its name derives from “kami o itsuki matsuru shima” which means “island dedicated to the gods” (Joseph Cali et al., 2013).

A record from 1168 states that a Shinto priest, Saeki Kagehiro has reconstructed the main shrine buildings, funded by the Heian Period (794-1184) most powerful leader, Taira no Kiyomori (1118-1181 CE) (ICOMOS, 1996). Its position in western Honshu placed it at the core of the Taira family’s mercantile and spiritual interests (Blair, 2013). The shrine’s layout, courtesy of Kiyomori, is still preserved to this day and consists of 56 interconnected wooden structures built on pillars above water. This architectural choice reflects several symbolic intentions: to prevent worshippers from spoiling the sanctity of the island, to serve as a reminder of the Buddhist belief that the dead crosses water to reach the afterlife, or to emulate the floating palace of the Dragon King popular in Japanese mythology (Cartwright, n.d.). Regardless of his intent, Kiyomori invested heavily to ensure the shrine was among Japan’s most magnificent, surviving long after the fall of his clan (Blair, 2013).

During the Kamakura Period (1185-1333), the main shrine buildings at Itsukushima were destroyed two times by fire, in 1207 and 1223, with the final reconstruction completed in 1241. Hereafter, reconstruction was done only on individual buildings (ICOMOS, 1996). Additionally, the shrine started honouring Benzaiten, goddess of love, literature, music and good fortune, revered by sea travellers and businessmen (Cartwright, n.d.).

By the late Muromachi Period (1233-1573), the island developed crucial commercial role due to its strategic location. Over time, the island’s sacred character diminished (ICOMOS, 1996). Warlord Mori Motonari reconstructed the honden in 1571, after previously desecrating it during the 1555 battle against Sue Takafusa (Joseph Cali et al., 2013). Gradually, residents and visitors were allowed, which attracted merchants, traders, and tourists, earning its recognition as “Japan’s Three Most Beautiful Sceneries (Nihon San Kei)” (Utaka, 2015).

In 1868, the Meiji government enacted new reformative laws, including designating certain sites as parks. The Shrine region became “Itsukushima Park”, which significantly influenced its social modernization. Additionally, the 1897 “Act for the Preservation of Shrines and Temples” included Itsukushima Shrine in its initial designations (Utaka, 2015). During this period, shrine and temple buildings were segregated by their Shinto or Buddhist affiliations, which led to the relocation of Benzaiten worship to the Daiganji temple close by and the destruction of some minor structures at Itsukushima (Cartwright, n.d.).

Figure 1. Daiganji Temple (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

A landslide behind Itsukushima Shrine in 1945 caused significant damage, with repairs lasting until 1957. This included efforts to mitigate future natural disasters, with protective structures cleverly concealed using traditional Japanese gardening techniques. Continuous conservation has been a priority since then (ICOMOS, 1996). The Shrine has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1996, an official National Treasure of Japan (Cartwright, n.d.).

Cultural context of the religion and architecture in Japan

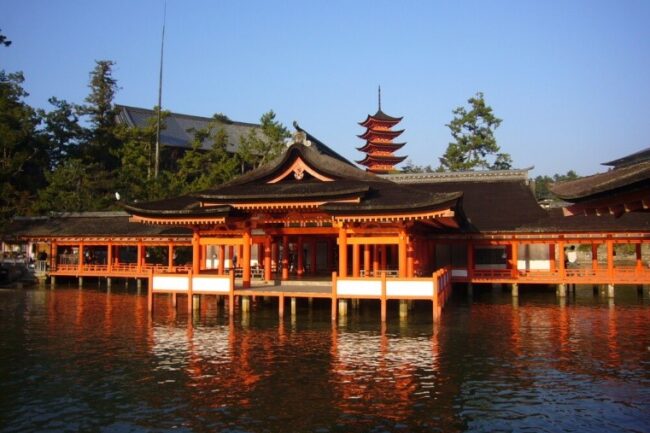

Throughout Japan’s history, Shinto and Buddhist architecture were influenced by each other, “creating an eclectic style of religious architecture” (Young et al., 2012), yet while keeping differences. Itsukushima Jinja exemplifies the scenic trinity typical of Shinto shrine architecture, with mountains in the background, the sea in the foreground, and man-made structures in the centre (ICOMOS, 1996). To understand Itsukushima Shrine means to explain the faith and the architectural culture in Japan that comes with it first.

Figure 2. Scenic view typical of Shinto Shrine, Miyajima in Aki Province (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Shintoism in Japan

Shinto has no founder or single scripture and emphasizes on practice over doctrine, with no set of moral rules, having a close tie with Japanese cultural identity and nature’s sacredness. It refers to customs centred on local deities where worship can be done either at home or at shrines (Deal, 2006).

Shinto is a polytheistic and pantheistic faith, where kami can manifest in everything that exists: in “organic and inorganic matter, and in actions beyond the control of man” (Joseph Cali et al., 2013). Some living individuals, such as the emperor, were venerated as kami, and rituals reinforced the imperial family’s divine right to rule. Kami can bring both blessings and disasters, and the religion in older times used offerings and prayers to mitigate the latter (Joseph Cali et al., 2013).

Another important concept in Shinto is tsumi, which can mean sin. However, the term originally meant ritual impurity (kegare), concerning the physical impurity from contact with death, blood or disease. Shinto rituals aim to restore purity after such contact (Deal, 2006). An architectural example can be torii gates, separating the outer profane world from the inner sacred space (Young et al., 2012).

Buddhism in Japan

China and Korea shaped Japan’s perception of the world until premodern times, as Buddhism became widespread in the country in the sixth century (Joseph Cali et al., 2013). In Buddhism, Buddha is viewed as a human who achieved enlightenment (nirvana) through spiritual practice, serving as a model for others (Deal, 2006).

A significant impact on Japanese culture, Buddhism not only formalized traditional beliefs into Shinto but was also affected by those beliefs. The attitude of native beliefs in Japan embraced Buddhism, which allowed people to worship both religions at the same time (Joseph Cali et al., 2013).

As Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa said, Buddhism influenced Japan the most through “the effects and methods of spatial composition and into ways of establishing relations between nature and architecture and between technology and humanity” (Kurokawa, Kisho, 1977).

Philosophy of Japanese architecture

Architect Yo-ichiro Hakamori notes that while Western cultures value the original stone blocks of ancient temples, Japan places greater importance on the craft and techniques passed down through generations rather than the permanence of the objects themselves (Ishida, Aki, 2015).

Kisho Kurokawa argues that wood-based cultures, like Japan’s, emphasize continuity and the natural characteristics of materials, unlike stone-based cultures. In stone-based cultures, materials are heavily processed and altered. He exemplifies this by claiming that Greek and Roman architecture would be the same with steel and concrete as with stone. Wood-based cultures develop techniques while working with the material when stone-based cultures are working against it, using walls to separate interior from exterior, treating buildings as mere containers for people. This traditional stone-based approach links to modern rationalism and functionalist architecture (Kurokawa, Kisho, 1977).

Wood construction is better at withstanding earthquakes than stone or brick due to its flexibility and shock-absorbing joints. Because of its poor conductivity of heat, it is safer than steel during a fire. This property also ensures a stable temperature throughout the year and resists sweating, making it “most suitable in a humid country like Japan” (Eike, Kiyosi, 1977). Additionally, native Japanese timber resists bacteria, fungi, and insects (Eike, Kiyosi, 1977).

However, wood still deteriorates over time. Japan has various solutions for this, such as the custom of periodic renewal, which also transmits the knowledge of the craft to the next generation for preservation. Another one is recycling materials from other buildings, remodelling, or restoring structures, or simply preserving them. Traditional Japanese joinery also allows the building to be nails-free for easier disassembling (Young et al., 2012).

The architecture of Itsukushima Shrine

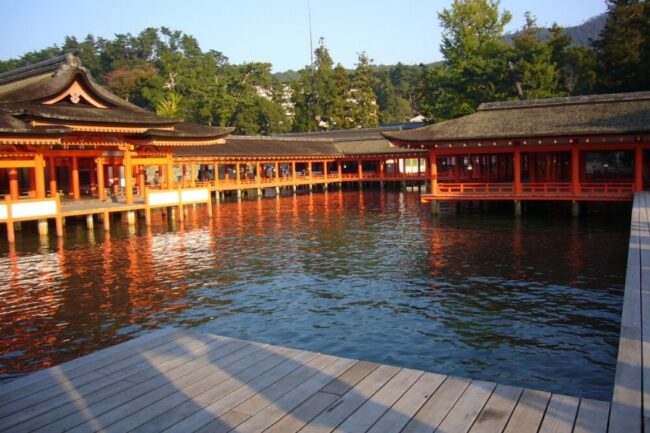

Itsukushima Shrine’s architecture follows the aristocratic Shindenzukuri style from the Heian Period (ICOMOS, 1996), featuring covered corridors crossing the shallow waters, connecting the main buildings to auxiliary shrines and stages, using natural materials. Built over a small inlet, at high tide, the shrine appears to float on the water, with its vermilion structures contrasting against the blue sea and green mountains (Dougill, John, 2014). Despite numerous repairs, the shrine has maintained its 12th-century character (Joseph Cali et al., 2013). The main shrine includes 37 buildings, while the outer shrine has 19 buildings along the shore (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

Figure 3. Itsukushima Shrine from the Torii (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 3. Itsukushima Shrine from the Torii (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

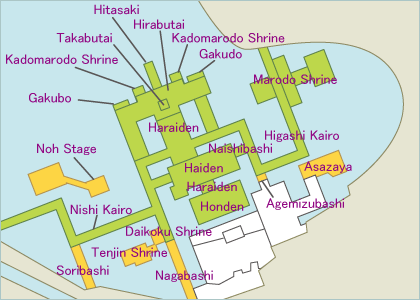

Figure 4. Layout of Itsukushima Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

Figure 4. Layout of Itsukushima Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

The shrine, designated an “Important Cultural Property”, faces increasing damage from sea exposure, typhoons, and decay of submerged foundation posts. Despite constant upkeeping, altering its architecture, like raising floor heights, is unfeasible to preserve its original beauty (Utaka, 2015). Maintenance includes tasks like algae removal and sandbar levelling. Remarkably, structures from 800 years ago are still standing (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.). Traditional anti-disaster measures, such as gaps in floorboards with no nails used for connecting corridors, help manage rising water pressure during high tides (Dougill, John, 2014).

Figure 5. The floorboards for mitigation of water (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

Figure 5. The floorboards for mitigation of water (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

East corridor (Higashi Kairo)

The East Corridor runs from the entrance of the ensemble, past the Marodo Shrine and Asazaya, to the Main Shrine’s purification hall. It is 4 meters wide and has 108 spans between pillars, one span being called “ma” in traditional Japanese architecture (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.). This concept of en-space is integral to Japanese fine arts, performing arts, tea ceremonies and architecture (Kurokawa, Kisho, 1977). In Japanese culture, Ma is not mere empty space, it refers to “the space or interval necessary to give shape to the whole” (Eike, Kiyosi, 1977).

Figure 6. East corridor (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

Figure 6. East corridor (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

Marodo Shrine

Before entering the shrine, visitors go to Haraiden (purification hall) to stand at Haraisho for spiritual cleansing. Only the purifying halls and main sanctuaries of the main and Marodo shrines have ceilings, which are “coved, coffered, and finely latticed”. Unlike the main shrine, the Marodo Shrine’s purification hall has an open front, exposing it to the sea (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

The Marodo shrine is second in rank and size to the Main Shrine. Subordinate to Itsukushima Shrine, it is dedicated to five deities (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

Figure 7. The ritual of purification at the Haraisho of the Main Hall (K, 2014)

Figure 7. The ritual of purification at the Haraisho of the Main Hall (K, 2014)

Figure 8. Marodo Shrine (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

Figure 8. Marodo Shrine (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.)

The Main Shrine

After the Meiji Restoration, chigi, “ornamental hornlike crossbeams on the gable of a shrine roof”, and katsuogi, “log-like elements on the ridge of a shrine roof” were added to the shrine, reflecting traditional Shinto architecture. These elements were later removed during major repairs in the Meiji and Taisho eras, restoring the original design. Now, the worship hall features a “three-ridged” style from the Nara Period (710-784) (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.). Like most structures at Itsukushima, the Honden has an eight-by-four bay structure, a kirizuma roof with cypress bark, white stucco walls, and a special fifteen-coat vermillion lacquer (Joseph Cali et al., 2013).

Figure 9. The Main Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 9. The Main Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 10. Kirizuma roof with cypress bark (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 10. Kirizuma roof with cypress bark (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 11. Inside Itsukushima Main Shrine

Figure 11. Inside Itsukushima Main Shrine

The purification Hall (Haraiden) of the Main Shrine

The purification hall served for monthly festivals and Bugaku, an Ancient Court Dance, during rainy days. Since the late Meiji era, it has hosted the “Year-end Market Forecast” to predict the upcoming year’s market conditions. The central front eaves are cut and elevated, a design feature common in late Heian period Amida Buddhist halls (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

Figure 12. Haraiden of the Main Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

Figure 12. Haraiden of the Main Shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

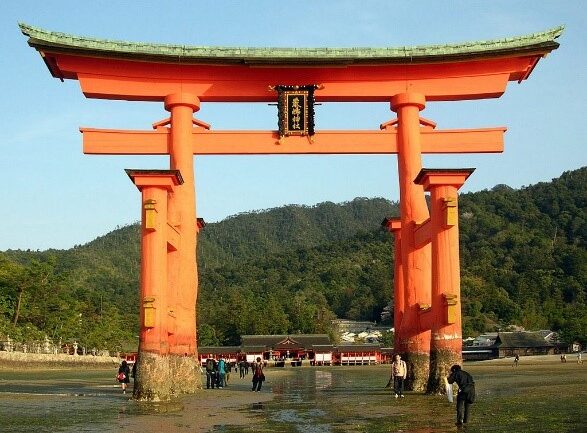

The Great Torii

Perhaps the most famous structure at Itsukushima Shrine, the Great Torii is standing 16 meters tall and weighing about 60 tons, 160 meters from the shore. Aligned with the shrine buildings and facing holy Mt. Misen, it was last rebuilt in 1875. Its giant pillars, made from 500-600-year-old camphor trees, appear deeply rooted like natural growths (Dougill, John, 2014). At high tide, it is designed to welcome worshippers arriving by boat, and at low tide, visitors can walk close to the 1,8-meter-wide column bases (Enscoe, 2009).

Figure 13. The Torii at low tide (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Figure 13. The Torii at low tide (“Itsukushima Shrine,” 2024)

Naga-hashi (Long Bridge)

Historically, these roofless bridges connected sea-based shrine buildings to the land. In the Edo period, an offertory room was set up on the south side of the Ushirozono, a back enclosure, to transport food offerings to the shrine (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

Figure 14. Naga-hashi (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

Figure 14. Naga-hashi (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.)

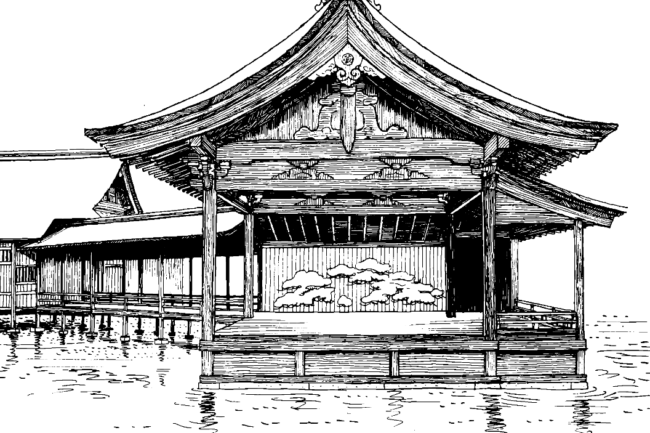

Noh Stage

In 1605, feudal lord Fukushima Masanori donated the shrine’s first permanent Noh stage. In 1680, Asano Tsunanaga built the current stage, the only Noh stage ever constructed over the sea. It features a thatched cypress roof and a single-board floor for resonance (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

Figure 15. Noh Stage (Nishii et al., 1999)

Figure 15. Noh Stage (Nishii et al., 1999)

West Corridor (Nishi Kairo)

The gable at the end of the West Corridor in the “Kara-hafu” (Chinese gable) style marks a corridor now of 194.5 meters long, previously 327 meters. The entrance, now the exit, was initially on the west corridor due to the old southern ship route before Taira-no-Kiyomori opened Ondo-no-Seto (“Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association,” n.d.).

Figure 16. The west corridor

Figure 16. The west corridor

Conclusion

Itsukushima Shrine stands as a testament to Japan’s rich spiritual culture and architectural heritage. Even though it has survived multiple socio-political changes since its founding, the shrine is continuously put in danger of destruction by natural disasters and fires (Utaka, 2015). Preservation of its construction techniques has become more crucial over the past century, as traditional Japanese architecture faces progressive abandonment, exchanging it for Western technologies.

References

Blair, H., 2013. Rites and Rule: Kiyomori at Itsukushima and Fukuhara. jas 73, 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1353/jas.2013.0002

Cartwright, M., n.d. Itsukushima Shrine [WWW Document]. World History Encyclopedia. URL https://www.worldhistory.org/Itsukushima_Shrine/ (accessed 5.10.24).

Deal, W.E., 2006. Handbook to life in medieval and early modern Japan, Facts on File library of world history. Facts On File, New York, NY.

Dougill, John, 2014. Japan’s world heritage sites: unique culture, unique nature. Tuttle Publishing.

Eike, Kiyosi, 1977. The art of Japanese joinery.

Enscoe, A., 2009. A Journey through Japanese Architecture, Old and New.

ICOMOS, 1996. Nomination of Itsukushima Shinto Shrine for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Paris.

Ishida, Aki, 2015. Paradox of a Landmark that is not: the life of the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Itsukushima Shrine, 2024. . Wikipedia.

Itsukushima Shrine | Sightseeing Spots | Miyajima Tourist Association [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.miyajima.or.jp/english/spot/spot_itsukushima.html (accessed 5.16.24).

Joseph Cali, John Dougill, Geoff Ciotti, 2013. Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion. University of Hawai’i Press.

K, K., 2014. Purifying mind and body at the Haraisho, before entering the Haraiden to pray – Itsukushima Shrine, Miyajima, Japan.

Kurokawa, Kisho, 1977. Metabolism in architecture. Studio Vista London.

Nishii, K., Hozumi, K., Horton, H.M., Nishii, K., 1999. What is Japanese architecture?, 5. ed. ed. Kodansha Internat, Tokyo.

UNESCO World Heritage, n.d. Itsukushima Shinto Shrine [WWW Document]. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. URL https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/776/ (accessed 5.17.24).

Utaka, Y., 2015. Managing “Buffer”: A Special Focus on the Itsukushima Shinto Shrine World Heritage Site, Japan. IRSPSD International 3, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.3.2_79

Young, M., Young, D., Yew, T.H., 2012. Introduction to Japanese Architecture. Tuttle Pub., Singapore.