Introduction

The city of Tel Aviv has the world’s largest number of buildings in the Bauhaus and International Style (Geva 2008), having its roots in the Bauhaus school in Germany and the modernism movement. Its rich history was rediscovered with the 1984 exhibition ‘White City. International Style Architecture in Israel: A Portrait of an Era’ (M. D. Levin 1984), which was held at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art for the 75th anniversary of Tel Aviv’s founding (Sonder 2016). This initiative prompted a vast number of preservation projects around the city, listing Tel Aviv as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

Historical background

While there have been numerous changes in Palestine and throughout the world at the beginning of the 20th century, the territory where Tel Aviv is now also underwent massive transformations. The first Jewish settlements in the area date back to the 19th century, when the first wave of immigrants came through the port of Jaffa, one of the two largest maritime gates in Palestine back in the day. Because even then Jaffa was already overcrowded, people sought shelter north of the city.

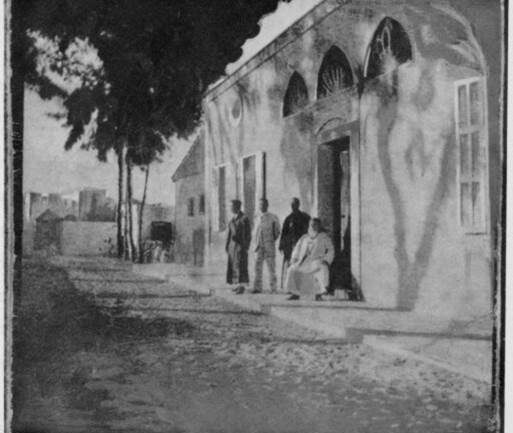

In 1883, Aharon Chelouche bought land north-east of Jaffa, where he built Chelouche House (Figure 1), the first house from Neve Tzedek, ‘the first Jewish neighborhood built outside of the walls of Jaffa’ (LTD n.d.). In the following years, other Jewish neighborhoods were established north of Jaffa.

Although Neve Tzedek has appeared first, Ahuzat Bayit is still considered to be the forerunner of Tel Aviv. The official date for the city’s founding was fixed at April 11, 1909 when 66 families participated in a seashell lottery to divide plots’ (Rotbard 2015), despite the fact that the neighborhood of Ahuzat Bayit itself was founded in 1906 (Rotbard 2015).

Figure 1: Chelouche House, Tel AvivLtd 2007

1909 seems more fitting to remember as the first crucial event in Tel Aviv’s history, as it remained a well-known story in the consciousness of the locals for decades. In 1910, the founders of Ahuzat Bayit decided to name it Tel Aviv (‘Hill of Spring’, a biblical town in Mesopotamia) (Azaryahu 2020), which later became the name of today’s city.

‘On 11 May 1921, Tel-Aviv obtained the status of “township” that implied a partial autonomy from Jaffa’ (Shoham 2011). Following the change from Ottoman to British authority and the start of ethnic-national conflicts in Palestine in the 1920s, in four years, Tel Aviv’s population tripled in size, leading to the development of tenements and inadequate housing (Allweil 2022).

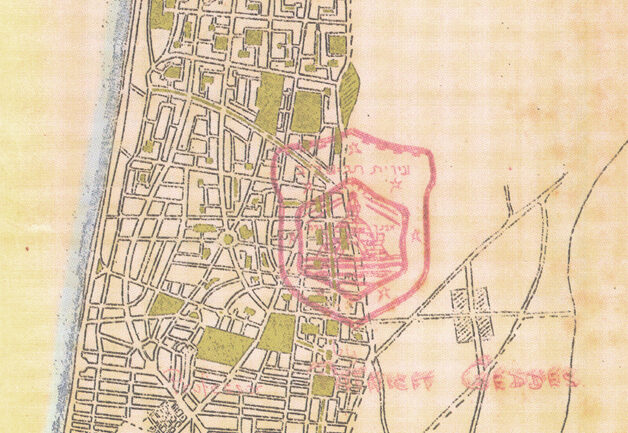

Figure 2: Geddes’s Plan for Tel Aviv and Jaffa, 1925 (Allweil 2022)

In 1925, Sir Patrick Geddes, biologist, social evolutionist and city planner (Sir Patrick Geddes n.d.), was tasked to design a ‘masterplan for the city’s development’ (Allweil and Zemer 2019) by the British High Commissioner

(Figure 2).

Geddes considered that urban planning cannot be ‘studied in one place and imitated elsewhere’ (Allweil 2022). As a result, in his survey report, he found that the two main paths dictated by housing development in Tel Aviv are the tenements and the ‘garden village’ plan solution, in the shape of a ‘housing before street’ process. Geddes found the second form of urbanism ‘remarkable’ (Allweil 2022), becoming the masterplan’s primary focus.

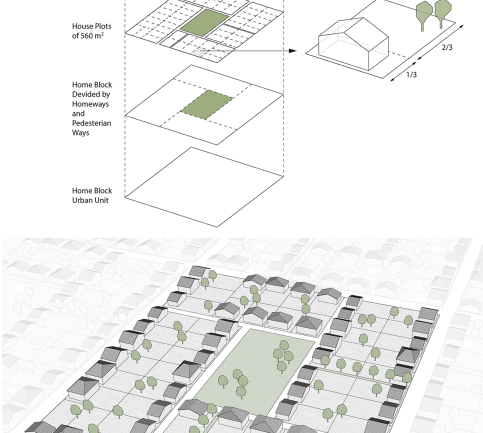

‘The whole plan, he stressed, “must be realized with the real and active participation” of the citizens’ (Allweil 2022), so that their needs can be addressed directly. The plan involved home blocks of various sizes that were all connected to one urban system. One home-block unit (Figure 3) consisted of self-sufficient ‘detached cottages with small gardens’ (Allweil 2022), built on one third of the 560 square meters plots, with a maximum height of 9 meters (Allweil 2022). There was also a small public park with communal facilities such as a playground and tennis court located within each block (Allweil 2022). ‘Geddes’ housing scheme was fully realized by the mid-1930s’ and it ‘allowed the city to grow and expand through war, independence and economic and social changes’ (Bucci and Mollo 2010).

Figure 3: Geddes’ Home Block Urban Unit (Allweil and Zemer 2019)

The rise of modernism and the Bauhaus School

The Industrial Revolution and the devastation caused by the First World War led to an urgent need for a change in architecture. Thus, the modernism movement induced a new way of thinking characterized by an emphasis on function, efficiency and technology.

On 1st of April 1919, Walter Gropius ‘became the head of the Kunstschule and Kunstgewerbeschule in Saxony (formerly directed by Henry van de Velde), which he merged into the institution known as the Staatliche Bauhaus, Weimar’ (Gorman 2003). Driven by the spirit of Deutscher Werkbund (The German Association of Craftsmen), Gropius encouraged Gesamtkunstwerk (”unified work of art”) (Shamir 2008). The students had to learn all artistic crafts ‘for art is not a “profession” ’ (Gropius 1919), in order to unify individual artistic vision and principles of mass production with the emphasis on function.

Among the Bauhaus professors were Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. But only by the appointment of Hannes Meyer in 1927, Bauhaus finally managed to have regular architectural education (Michael and Lutz 2009).

In 1925, the school had to move in Dessau as a result of political pressure. Following the resignation of Gropius and the discharge of Meyer, Bauhaus moved to Berlin in 1932 under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s administration. The next year, when the Nazi Party came to power in Germany, the police closed the school. Even though Mies had tried to reopen the faculty, ‘economic and, primarily, political reasons made continuation impossible’ (Michael and Lutz 2009). Bauhaus was forever closed on the 20th of July 1933 (Michael and Lutz 2009).

Since its closing, students and teachers of the Bauhaus school have fled all over the world, especially the United States, the USSR, but also Palestine.

The International and Bauhaus Style of Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv is known for its approximately 4000 buildings designed in the International Style (UNESCO 2003), most notably by the four architects who studied at Bauhaus and came to Palestine.: Shlomo Bernstein, Munio Weinraub Gitai, Shmuel Mestechkin and Arieh Sharon (Rotbard 2015). Other important modernist architects in Tel Aviv were Genia Averbuch, Dov Karmi, Richard Kauffmann and Erich Mendelsohn (Schuler 2019).

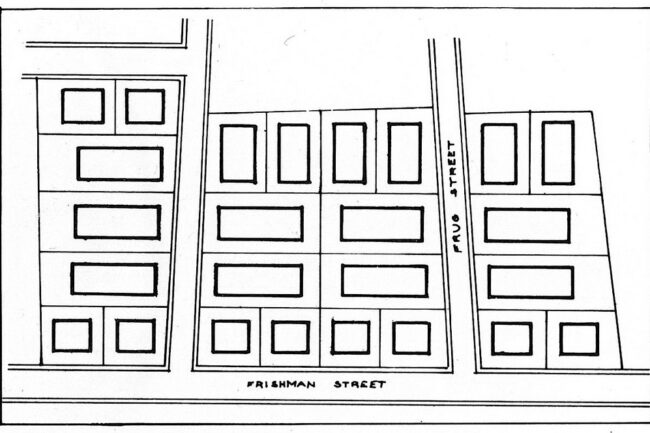

Before the appearance of modernism in Tel Aviv, the buildings were designed in ‘a collection of various architectural styles’ (UNESCO 2003) which combined local Oriental motifs, decorative elements from Jewish tradition (Figure 4), referred to as the Eclectic Style (UNESCO 2003). The architecture at the time was intended that way so it ‘would not be alien to its surroundings but rather carry on the long tradition of local architecture . . . a continuation of the 19th-century world-wide architectural trend’ (M. Levin 1982).

Figure 4: Palm House in Eclectic Style, Tel Aviv (Browns 2010)

1926 to 1928 were years of crisis, and by 1929, construction regained speed. The new buildings were mainly influenced by Art-Deco. Decorative elements were reduced, marking ‘the transition between the Eclectic Style

and the Modern Architecture of the thirties’ (UNESCO 2003).

‘Arieh Sharon in particular later recalled how “shocked” he was after his return to Palestine in 1932’ (Sonder 2016), seeing the chaotic architecture, so he considered ‘the time was ripe for “architectural revolt” ’ (Sonder 2016).

When the Nazis rose to power in Germany in the 1930s, many Jewish people escaped to Palestine, including architects taught at Bauhaus and other Central European schools. Many agreed that the Bauhaus Style in Tel Aviv looked ‘perfectly adapted to its new setting’ (Szmuk et al. 2004).

Therefore, modernism, a popular movement at the time in Europe and the United States and at the opposite political spectrum with Nazi Germany, matched Tel Avivian views and needs. Leaving everything behind, most Jewish immigrants refused to bring their old customs to start a new life in Palestine. Rejecting traditions and embracing technology are the main principles of the International Style, hence its name.

The ensemble of modernist buildings in Tel Aviv is commonly known today as the ‘White City’. The term mainly comes from the association of the color they are wearing. Not only a minimalist statement like in other parts of the world, white has a vital use in the Mediterranean climate, to protect buildings from the heat (Poon 2020).

However, a futuristic vision and white facades are not the only Bauhaus principles that Tel Aviv’s modernist buildings follow. Simple, organic forms, ‘without romantic gloss and wasteful frivolity’ (Gropius 1926), accessible flat roofs, abolition of the separating function of the wall, ribbon windows and the usage of reinforced concrete with silicate blocks can also be found.

Moreover, Tel Aviv’s buildings are unique because of the hot and humid climate. The long balconies, small windows (Figure 5) and open plan design are all due to their specific location. The first floor is also built on ‘pilotis’, part of Le Corbusier’s five points of architecture, to provide shade (Geva 2008). According to Arieh Sharon, ‘the greatest influence on Tel Aviv has always been Le Corbusier’ (Rotbard 2015).

Zeev Rechter first introduced ‘Corbu’s pilotis (pillars) into – or rather under – Tel Aviv’s dull townscape’ (Sharon 1976) in 1934 with Engel House (Figure 6), which became a very popular design solution in the area. Arieh Sharon would later on name Tel Aviv ‘A Town on Pilotis’ (Sharon 1976).

There are 3 types of Bauhaus buidings in Tel Aviv: public buildings (e.g., Esther Cinema, Jacobson’s Building), tenements for workers (e.g., HodWorkers’ Residence, Meonot Ovdim complex) and upper-middle class residential houses (e.g., Max Liebling House, Krieger House, Leon Recanati House).

Figure 5: Esther Cinema, Tel Aviv (Center 2020)

Following Geddes’ Garden city plan, though with improved standards, the biggest number of buildings were residential houses (Sonder 2016). From Sharon Rotbard point of view, the ‘only local, Bauhaus-trained architect to conclusively leave his mark on Tel Aviv (and arguably on Israel as a whole) was Aryeh Sharon’ (Rotbard 2015).

Arieh Sharon

Arieh Sharon was born in Jaroslaw, Poland in 1900 (Arieh Sharon 2022). In 1920, he settled in Palestine where he worked as a builder on Kibbutz Gan Shmuel. From 1926 to 1929, he studied at Bauhaus under Walter Gropius and Hannes Meyer.

Sharon supervised the general building of Meyer’s Bundesschule and Berlin office from 1929 until 1931 and by 1932 he won the design competition in Tel Aviv with his first commission, the four Histadrut Pavilions in the Middle East Levant Fair (Shamir 2008). ‘Though invited to work with Meyer and Mart Stam in Magnitogorsk in the USSR he chose to remain in Tel Aviv where he and two architects Ze’ev Rechter (from Corbusier’s office) and Joseph Neufeld (from Mendelsohns office) formed the ’Chug’ or ’group/circle’ of architects to discuss and debate design ideas, material and methods and the development of a modern architectural in ’Eretz Israel’ ’ (Shamir 2008). Later on, he ‘was appointed head of Israel’s first national planning office in 1948, and was awarded the Israeli Prize for Architecture in 1962’ (Sonder 2016).

Figure 6: Engel House, Tel Aviv (Center 2020)

Throughout his life, he designed ‘numerous schools, hospitals, housing complexes, kibbutzim and later comprehensive town and settlements plans’ (Shamir 2008). His work was heavily inspired by his experience of living on kibbutz and studying at Bauhaus (Figure 7). In ‘Kibbutz + Bauhaus: An architect’s way in a new land’ Sharon wrote that ‘In some ways, life at the Bauhaus reminded me of the kibbutz, where the youngsters tried to get rid of conventional ties and to create a new productive style of living’ (Shamir 2008).

Figure 7: Clubhouse for the workers of the Agricultural Research Station, Rehovot (1934) (Yael Aloni 2011)

Figure 7: Clubhouse for the workers of the Agricultural Research Station, Rehovot (1934) (Yael Aloni 2011)

Though both Walter Gropius and Hannes Meyer, mentors of Arieh Sharon, had a socialist view on architecture, Meyer was more radical, extending Gropius’ philosophy by ‘reducing the act of building to the physical act of building’ (Wang 2014). This influenced Sharon’s style to a greater extent, which compared to the other modernist architects in Tel Aviv, he focused more on the ‘social and human architectural problems, instead of concentrating on aesthetics and form in design’ (Sharon 1976). As Sharon Rotbard would say, Arieh Sharon’s ‘straightforward and pragmatic structures have always been at odds with the stylized boxes which have come to be associated with Tel Aviv’s Bauhaus Style’ (Rotbard 2015).

Meonot Ovdim

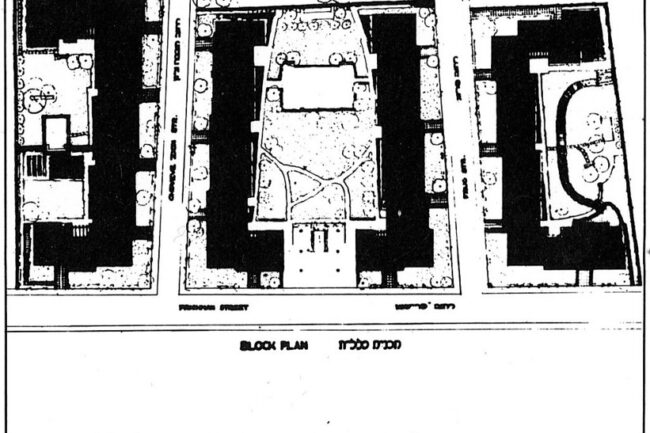

Arieh Sharon’s housing estate, Meonot Ovdim (Figure 8), was awarded first prize in Histadrut’s (General Organization of Workers in Israel) (Yael Aloni 2011) architectural competition for its innovative housing solution for the rapid growing population (Figure 9, Figure 10).

Figure 8: Meonot Ovdim Estate in the 30s (Yael Aloni 2011)

Built in 1935, it consisted of 150 flats. Following Gropius’ principle of ‘simplicity in multiplicity’ (Gropius 1926), the ensembles of ‘continuously staggered’ (Yael Aloni 2011) apartment blocks enclose large garden patios in their center, ‘a convention of Arab-style building around the Mediterranean’ (UNESCO 2003). Known as ‘the workers’ fortress’ (UNESCO 2003), the estate provided all necessary services for an independent ‘communal social life’ (UNESCO 2003): the lower floors were planned to consist of a clinic, laundry (UNESCO 2003), ‘cooperative shops, kindergartens, reading-rooms and club-rooms, located around the interior courtyard and joining the garden areas’ (Yael Aloni 2011).

Figure 9: Old ’Garden City’ Layout (Yael Aloni 2011)

Figure 10: Meonot Ovdim Layout, Tel Aviv (Yael Aloni 2011)

Slightly set back from the streets, the buildings provide greater widths for sidewalks, allowing the greenery to become the bridge between public and residential. The apartment blocks facing south towards Frishman Street stand on columns (Figure 11). This creates shaded open spaces connected to the inner courtyard via a wide entrance area, allowing plenty of light and ventilation, while also creating privacy for tenants.

Figure 11: The Entrance to the Interior Garden from Frishman Street (Google 2023)

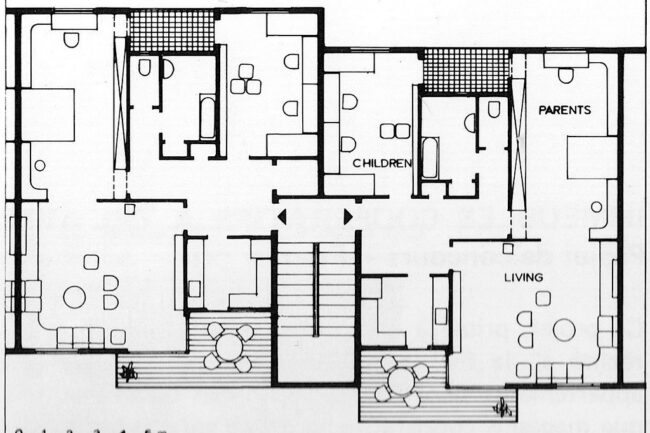

For one family, the estate’s size of the living quarters was considered a modern standard, though it can still be applied today (Figure 12). By mirroring the apartments across the axis of a shared staircase, while also moving them back one by one, Arieh Sharon managed to create a systematic, ‘rhythmic architecture’ (Wang 2014).

Figure 12: Meonot Ovdim Apartment Plan (Yael Aloni 2011)

However, ‘the uniformity of the cells’ (Gropius 1965) was not to last. At this time, Arieh Sharon’s Meonot Ovdim has changed considerably. People modified their balconies however they desired, leaving the facades almost unrecognizable and questioning Gropius’ adequacy of standardization (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Meonot Ovdim Estate Now (Google 2023)

Conclusion

The Bauhaus architecture in Tel Aviv is a unique and influential example of modern design that reflected the city’s past socio-political needs, redefining traditional perspectives on the implications of universalism in terms of context, site-specificity and architectural relevance, while also creating a new vernacular to the city.

References

Allweil, Yael (2022). “Housing Before Street: Geddes’ 1925 Anarchist Plan For Tel Aviv”. In: (). url: https : / / www . academia . edu / 9344597 / _Housing_Before_Street_Geddes_1925_Anarchist_Plan_For_Tel_ Aviv (visited on 12/17/2022).

Allweil, Yael and Noa Zemer (2019). “Housing-Based Urban Planning? Sir Patrick Geddes’ Modern Masterplan for Tel Aviv, 1925”. In: Urban Planning 4.3, pp. 167–185.

Arieh Sharon (Aug. 2022). en. Page Version ID: 1103799064. url: https: //en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php title=Arieh_Sharon&oldid= 1103799064 (visited on 12/13/2022).

Azaryahu, Maoz (2020). Tel Aviv: Mythography of a city. Syracuse University Press.

Browns, Shmuel (2010). Eclectic Style Architecture. url: https://israeltourguide. info/2010/12/09/eclectic-style-architecture/.

Bucci, Alessandro and Luigi Mollo (2010). Regional architecture in the Mediterranean area. Vol. 8. Alinea Editrice.

Center, The White City (2020). Tel Aviv City Guide: 6 Bauhaus Buildings to See in the White City. url: https://www.archdaily.com/932625/telaviv- city-guide-6-bauhaus-buildings-to-see-in-the-whitecity.

Geva, Anat (2008). “Rediscovering sustainable design through preservation: Bauhaus apartments in Tel Aviv”. In: APT bulletin 39.1, pp. 43–49.

Google (2023). Frishman St 35. url: https://www.google.com/maps/ place/Frishman+St+35,+Tel+Aviv Yafo,+Israel/@32.0799027,34. 772358,149m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x151d4c78be30f0e5: 0x1e922b9f76f1c7ab!8m2!3d32.0799016!4d34.7729065?hl=en.

Gorman, Carma (2003). The industrial design reader. Skyhorse Publishing Inc.

Gropius, Walter (1919). “Bauhaus manifesto and programme”. In: Weimar: The Administration of the State Bauhaus at Weimar.

— (1926). “Principles of Bauhaus production [Dessau]”. In: Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-century Architecture, pp. 95–97.

— (1965). The new architecture and the Bauhaus. Vol. 21. MIT press.

Levin, Michael (1982). “East or West: Architecture in Israel 1920-1933”. In: Scheps, Marc, The Twenties in Israeli Art (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum, 1982), exhibition catalogue, pp. 219–232.

Levin, Michael D (1984). White City: International Style Architecture in Israel, A Portrait of an Era. Tel Aviv Museum.

Ltd, Amnon Bar Or – Tal Gazit Architects (2007). Shloush St., Tel Aviv-Yafo – Beit 32. url: https://www.amnon-baror.co.il.

LTD, Bein Harim Tourism (n.d.). Neve Tzedek. url: https://www.beinharimtours.com/neve-tzedek/.

Michael, Siebenbrodt and S Lutz (2009). Bauhaus 1919-1933. Parkstone International.

Poon, Stephen TF (2020). “Myth of International Style: 20 th-Century Architectural Modernism and Bauhaus Design in Modernisation of Urban Cities”. In: Journal of Fine Arts 3.3, pp. 09–19.

Rotbard, Sharon (2015). White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Pluto Press London.

Schuler, Ronny (2019). “Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine”. In: International Journal of Architectural Theory 24.39, pp. 11–33.

Shamir, Adi (2008). Bauhaus Style: The Architecture of Hebrew Labor in British Mandate Tel Aviv, Palestine. University of California, Berkeley.

Sharon, Aryeh (1976). Kibbutz+ Bauhaus: an architect’s way in a new land. Karl Kramer Verlag GmbH Co.

Shoham, Hizky (2011). “Tel-Aviv the First Century: Visions, Designs, Actualities”. In: Indiana University Press. Chap. Tel-Aviv’s Foundation Myth: A Constructive Perspective, pp. 34–59.

Sir Patrick Geddes (n.d.). doi: 10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095845734. url: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority. 20110803095845734.

Sonder, Ines (2016). “Bauhaus architecture in Israel: de-constructing a modernist vernacular and the myth of Tel Aviv s ≪White City≫”. In: Handbook of Israel: major debates. Berlin, pp. 87–101.

Szmuk, Nitza Metzger et al. (2004). Dwelling on the Dunes: Tel Aviv, Modern Movement and Bauhaus Ideals.

Ulrichsen, Kristian Coates (2018). Balfour Declaration. doi: 10.1093/acref/ 9780191835278.013.0055. url: https://www.oxfordreference.com/ view/10.1093/acref/9780191835278.001.0001/acref-9780191835278- e-55.

UNESCO (2003). “White City of Tel-Aviv—The Modern Movement”. In. Wang, Brandon (2014). Within Contexts: Arieh Sharon and Bauhaus Universalism. for Eric Anderson’s Seminar: The Bauhaus at RISD. url: https://www.academia.edu/7284280/Within_Contexts_Arieh_Sharon_and_ Bauhaus_Universalism.

Yael Aloni, Ariel Aloni (2011). Arieh Sharon Architect. url: https://www.ariehsharon.org.